August 20th, 2010 ~ Ray Lee ~ No Comments

See Bridge Jeopardy by Ray Lee for quiz questions.

1. Harold S. Vanderbilt

2. Joseph B. Elwell. Like Culbertson, Elwell had a bridge-playing wife, who was arguably the stronger player of the two. Elwell’s wife may well have been the real author of most if not all of his books.

3. Contract Bridge Blue Book. He followed later with a Red Book and Gold Book, which also did well, but the Blue Book was far and away the most popular.

4. The number of cards they held in the heart suit.

5. The Smother Squeeze does not yet exist; the rest are real.

6. George Burns. Chico Marx was another comic who played bridge, and in fact appeared on Goren’s TV show.

7. Bill Anderson. (If you got that one right you are a real bridge history buff, and/or you live in Toronto.)

8. Helen Sobel, who should be fondly remembered for this remark alone, never mind the dozens of great hands she played.

9. The reference is from Lewis Carrol’s The Walrus and the Carpenter. ‘A pleasant walk, a pleasant talk, along the briny beach; we cannot do with more than four, to give a hand to each.’

10. This was a trick question — they ALL were!

August 11th, 2010 ~ Ray Lee ~ 12 Comments

I’ve stolen the title for this blog from a forthcoming MPP book, which just happens to be a novel revolving around cheating at bridge, the difficulty of proving it, and the conundrum of what to do with the culprit(s) when it is finally proven. I wanted to comment on an incident in the New Orleans Spingold, which has already been the subject of much discussion and controversy on various bridge forums.

First, the deal in question:

You are playing the round of 64 in the Spingold against a much higher seed. You start the second quarter about 40 behind, and this board comes up early on:

♠ — ♥ A x x ♦ A Q x x ♣ A K Q 7 x x

You are red against white, and RHO opens 3♠. Your call.

No, this isn’t a quiz; that was just to give you a moment or two to think about how you might proceed. What happened at the table was the holder of this hand, Howard Piltch (a professional player but not a top-ranked expert), bid 6♦ . This was a dramatic winner when dummy hit with essentially king fourth of diamonds and out and both minors behaved well.

There’s a lot of to-ing and fro-ing on the forums, but let me try to distil it at least into what is undisputed in terms of further facts.

1) At no stage did Mr. Piltch claim that his bid had been a mechanical error or some other kind of accident. His partner claims it was a ‘state of the match’ attempt to generate a swing.

2) The boards were dealt at the table, apparently with all four players present. Mr. Piltch made only one board of the eight, which he remembers as being Board 8 (not the one in question).

3) The director was consulted at some stage by the opposing team, but did not change the table result. The opposing team did not lodge an appeal (they won the match by more than 100 IMPs) but did express an intent to pursue the matter in a Conduct and Ethics hearing.

This, you will I’m sure recognize, leaves many questions unasked and a great deal of information ungathered, which makes the whole ‘Was he or wasn’t he?’ discussion somewhat academic. So I’m not going to go into that at all. However, there are some possibly new points that are perhaps worth making here.

First, since this was a dealt board, and had not yet been played at the other table, presumably the only direct cheating method available would be introducing a stacked deck. Lest you feel this is unlikely, let me mention that there have been at least two well-proven cases of deck-substitution in the Toronto area alone. One of the perpetrators, after being banned, later showed up playing on OkBridge – using two different user accounts and playing in partnership with himself, incognito, to improve his rating. Once a cheater…

Second, how much evidence is required to convict a player of cheating? This is where bridge courts separate from real life. Alan Truscott (in The Great Bridge Scandal) remarks that it’s very difficult to prove cheating from hand records, but that it is possible to prove the reverse. Terence Reese, in his apologia Story of an Accusation, understandably argues that the hands tell the tale in either event. Reese was of course famously acquitted after a judicial hearing presided over by a non-bridge-player, who applied the ‘beyond reasonable doubt’ standard to the case. Allan Falk, an expert bridge player and also a prominent Michigan attorney, wrote a fascinating essay for the MPP edition of TGBS, in which he points out that nowhere except in criminal courts is this standard applied. Elsewhere, in both sports tribunals and real life (and O.J. Simpson’s first two trials are a well-known example), the test is ‘preponderance of the evidence’. So too it is (or should be) with bridge.

Third, and perhaps most interestingly, is the issue of whether Mr. Pitch’s past record should have any bearing upon people’s willingness to believe him guilty of some kind of wrongdoing in this instance. The question of prior record is another where we needs must part company with criminal procedure. The previous convictions of the accused are not revealed in court until a conviction has been recorded, and are taken into consideration only for the purposes of sentencing. However, in bridge, one instance alone is rarely enough to convict.

Arthur Clarke once wrote that any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic. So when the disparity in ability between players is great enough, the lesser mortals will find it difficult to understand how the experts get to the right spot, and make brilliant leads and plays, apparently ‘seeing through the backs of the cards’. Eventually the experts may even be suspected of cheating. ‘Strange’ bids too can attract accusations, yet bidding is far from an exact science (look at any magazine bidding panel, and you’ll see 30-odd experts all arguing vehemently that five different bids are each the only correct action). So much is ‘style’, or even table feel. It is when actions deemed ‘unusual’ work out a high percentage of the time, or when a player finds the brilliant lead on just too many occasions, that antennae start to quiver – and when probably something is indeed going on. Any single occurrence may mean nothing – a lucky guess, an opponent flashing his hand, a flight of fancy that happened to work, or some such. It is the multiple, as these incidents repeat themselves, which begins to make the case – and since we so often play against different opponents, it takes a while for anyone to notice.

Thus we have the ‘Recorder’ system, and the ability to look at a player’s track record of unexplained incidents, a record that taken as a whole may add up to an unappetizing picture. As one forum poster put it, “If I were a judge in a bridge matter and the facts as presented came before me to make a ruling without revealing the identity of the 6♦ bidder, I would be highly doubtful that there could be any innocent explanation of the events that unfolded. And, if I was told that the person who bid 6♦ on this hand was the person who is being discussed above, that would end all doubt for me.”

In the words of Ian Fleming, ‘Once is happenstance; twice is coincidence, and three times is enemy action.’

August 10th, 2010 ~ Ray Lee ~ 9 Comments

Barry Rigal introduced me to a real time-waster in the Press Room a couple of world championships ago – a web site called Sploofus. Now unfortunately defunct, it consisted of a fantastic collection of trivia and word games, which grew organically through constant member contributions. At one point, I was inspired to develop a bridge quiz for Sploofus, which (blush) got an Editor’s Award. Since the site is no longer there, I thought I’d recreate it, with some modifications, for this blog. No prizes – you can Google the answers in 5 minutes – the trick is to see how many you can get right off the top of your head. Since this blog has a bridge-savvy readership, I’ve made it a little harder: the original was multiple choice, but for this one, you’re mostly on your own. I’ll post the answers in a few days.

Enjoy!

1. The exact origins of bridge are murky, although it obviously derives from whist and its precursors. The trail runs through games such as plafond and biritch, finally arriving at auction bridge and then contract. The game as we know it today came into being when an American millionaire invented a new scoring table during a New Year cruise on the SS Norway, in 1927-8. With only minor changes, we still use his scoring today. Who was he?

2. Some of the pundits of auction bridge, like Milton Work, made the transition to contract, and continued to play, teach and write about the new game. One of the most prolific early auction/contract authors became notorious when he was found dying of a gunshot wound in his NY townhouse in 1920, a murder which has never been solved. It was the subject of a Philo Vance mystery novel by S.S. van Dine: in fact The Benson Murder Case suggested a possible solution. Who was the victim?

3. Ely Culbertson was the first great promoter of bridge: he founded a magazine (The Bridge World), a bidding system, conducted newspaper columns and radio shows, and wrote dozens of books. The final pages of his first book were dictated in a cab on the way to catch a transatlantic liner, which was to take him to play a challenge match in the UK. The book, the first description of his methods, went on to sell millions of copies, making it comfortably the all-time best-selling book on the game. What was its title?

4. The bridge world was stunned in 1965 when Terence Reese and his partner Boris Schapiro were accused of using illegal finger signals at the world championships in Buenos Aires. The case generated controversy for years, not least because they were exonerated (or at least the charges were declared ‘not proven’) after an enquiry by a non-bridge-playing judge in the UK. Today it is generally accepted that they were indeed cheating. What information did the partners convey to one another?

5. Which of the following is not a type of squeeze?

Clash squeeze

Entry squeeze

Hexagonal squeeze

Knockout squeeze

Mole squeeze

Smother squeeze

6. Many celebrities have been keen bridge players, including more than one US President and First Lady. One of the best-known was this comedian, who was still playing cards at his country club a few days before his death at a very advanced age. He was born Nathan Birnbaum; what was his stage name?

7. Ely Culbertson’s successor as ‘Mr. Bridge’ was Charles Goren, who promulgated Point Count Bidding, an easier method than Culbertson’s system based on Honor Tricks. Yet the Goren System was not invented by him: it owed much to Milton Work and Bryant McCampbell, but the final touch, the addition of distributional points, came from a Toronto actuary. What was his name?

8. One of Goren’s favourite bridge partners was perhaps the best woman player of all time. When a kibitzer asked her one time what it was like to partner one of the world’s great players, she snapped, ‘I don’t know – why don’t you ask Charlie?’ Who was she?

9. Far and away the liveliest and most readable history of contract bridge from its beginnings to the early 1950s was penned by Irishman Rex Mackey: The Walk of the Oysters. The title is a reference to a line in a literary work… from which of these authors? For a bonus point: what does the line have to do with bridge?

Lewis Carroll

T.S. Eliot

James Joyce

William Shakespeare

G.B. Shaw

10. Ira Corn’s sponsorship of the Aces changed bridge forever, and ushered in the era of professional teams. The makeup of the squad changed several times over the years. Which of the following players was never a member of the Aces?

Fred Hamilton

Eddie Kantar

Mike Passell

Paul Soloway

Alan Sontag

John Swanson

August 2nd, 2010 ~ Ray Lee ~ 11 Comments

Driving home last week from New Orleans, our route took us directly through Memphis, so we decided to make an overnight stop there for two reasons. One was to sample the local BBQ once again; Brent Manley sent us to Corky’s, which was a great choice – the lineup moved quickly and efficiently, while we inspected the celebrity pictures on the walls, everyone from Bill Clinton and Margaret Thatcher to Elvis’s martial arts instructor seems to have been there at some time. The food was great – and it isn’t even Brent’s favourite spot; that’s the Rendezvous, which wasn’t open on a Sunday night. We made a mental note to return next year and try it – if it’s better than Corky’s, it must really be something.

Our second motive (ignoring Linda’s determination to empty the local clothes stores) was to see the spiffy new ACBL HQ at Horn Lake (just outside Memphis), and especially the new Bridge Museum, that both Brent and ACBL boss Jay Baum had told me was well worth a visit.

With most of the ACBL folks in New Orleans, Dave Smith (“Memphis Mojo”) was one of the few left behind to hold the fort, and as it turned out, to kindly take the time to lead us a on a tour of the building. Eventually we let him get back to work, and he abandoned us in the museum, where we spent the next couple of hours.

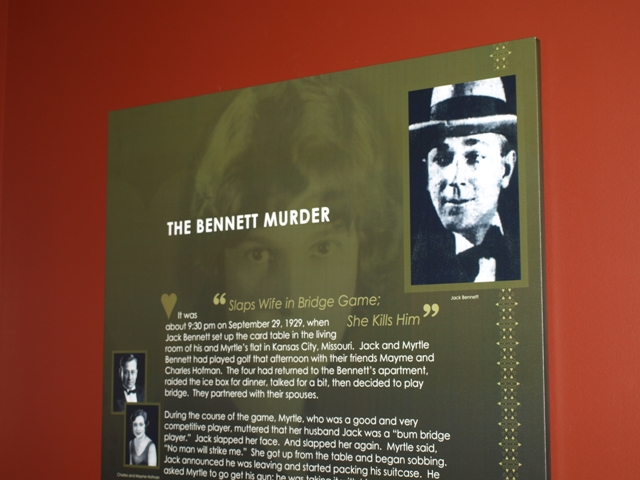

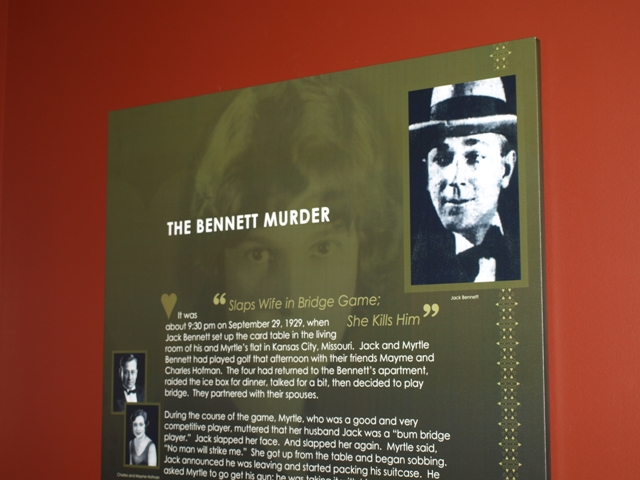

You’ll be able to get a sense of it from the photos that accompany this blog, but let me start by saying that the presentation is first-class. The highlights of bridge history are traced from their beginnings: Vanderbilt and the invention of the new scoring table, Culbertson, Goren (both of whom had TV shows, which are available for you to watch).

-

I I Isuppose it was inevitable that the Bennett murder would be included, but at least the write-up emphasized that its real importance was the way Culbertson was able to use the publicity surrounding the case to market the game. I I Isuppose it was inevitable that the Bennett murder would be included, but at least the write-up emphasized that its real importance was the way Culbertson was able to use the publicity surrounding the case to market the game.

There’s some fascinating memorabilia showcased, from an ace of spades that travelled on a US space mission to antique duplicate boards, one of the earliest LM cards, and even long-playing records from which people could get bridge lessons and tips. Joan Schepps’ incredible collection of trump indicators is beautifully displayed – I really like these strange little artifacts, I’m not sure why. Joan Schepps’ incredible collection of trump indicators is beautifully displayed – I really like these strange little artifacts, I’m not sure why.

The interactive displays (‘My Favorite Hand’ and the Hall of Fame) unfortunately weren’t working when we went through, but from the description we got they both sounded very well done – I would very much have liked to watch some of the interviews with the Hall of Famers. Ah well, have to leave something for next time!

Finally we checked out the library, which has some interesting items – including one of the few complete sets of The Bridge World in existence, as well as a complete run of World Championship books from 1953 onwards.

I hope I’ve done enough to convince you that the Museum is well worth a visit – even if you have to go a bit of your way. I’ve done my share of ACBL-bashing in print over the years, so let me be fair and applaud when they have done something well, which is certainly the case here.

Enjoy the photos:

The Joan Schepps trump indicator collection

July 3rd, 2010 ~ Ray Lee ~ 10 Comments

Quite a lot of the discussion on this site focusses on rulings and appeals. Some of the posters are interested in justice — applying the law as correctly as possible. Others are more interested in equity — trying to restore (if possible) the correct bridge result, while assessing any transgression penalties as a separate issue. The difference between these two approaches could not have been illustrated better than in today’s FIFA World Cup quarterfinal match between Uruguay and Ghana.

For those who are not familiar with what occurred, the match went to extra time. In the last seconds of that, there was a goalmouth flurry at the Uruguay end, during which Luis Suarez of Uruguay deliberately handled the ball to prevent it going into the net for the winning goal. (This description of what occurred is not the subject of any controversy — he handled the ball on purpose, and without that action, Ghana would have scored.) The ref applied the rules quite correctly: he sent off Suarez, and awarded Ghana a penalty kick, which would be the last action before the final whistle. Justice was therefore served. Now I’m not sure what the stats are on scoring from penalties in the World Cup ( in normal pro play they run around 70-80% I think), but the Ghana striker (under severe pressure one would think) slammed the ball against the crossbar instead of into the back of the net, and the match therefore ended in a draw. This was followed a tie-breaking penalty shootout (always a lottery), which Uruguay won.

So here we have a situation where a player deliberately breaks the rules in the most flagrant of fashions, and derives a benefit from so doing. Justice? Maybe. But certainly not equity. Ghana should have won, and but for the one of the most appalling acts of World Cup cheating since Maradona’s infamous ‘Hand of God’ goal against England they would have done so. Now you could argue that Ghana should have scored from the penalty — but penalty kicks are far from 100%, and why should they be put in that position? It’s the same argument used by the USBF Trials committee in my last blog, who ruled after a fairly gross CD incident that the non-offending side ‘should have figured it out’. Sorry, guys — I don’t see why they should have to.

It’s interesting to compare the attitudes in different sports to this kind of thing. Rugby, for example, in an analogous situation, allows the ref to award a penalty try (think touchdown), AND penalize the offender — a great example of justice and equity both being served. Basketball, on the other hand, is quite blase about deliberate fouling as a tactic towards the end of a game, which is one reason I never watch it.

Perhaps bridge committees could do better in their decision-making by applying this very simple precept: you should never be able to gain an advantage by breaking the rules of the game.

June 21st, 2010 ~ Ray Lee ~ 16 Comments

| This was board 44 of RRII in the current USBF Team Trials. The players involved were: North John Hurd South Joel Wooldridge West Renee Mancuso East Sheri Winestock. East’s

The result: 5♥ doubled by South making… +650 N/S

The director was called after the hand. South asserted that he would not have doubled 5♥if he was given the same explanation as his partner. He would have

passed since their agreement was that this would be a forcing auction. He’d leave it to partner to make the decision to bid 5♠ or double… sure that partner would

bid 5♠ on the hand he held. He did not believe that the same forcing auction rule would apply with 3♦ being a weak jump shift rather than a preemptive raise.

The committee (Bill Pollack, chair; John Sutherlin; Robb Gordon) upheld the director’s ruling: Result stands.

The committee felt that, despite the incorrect explanations that South was given, no matter which explanation he wanted

to believe about East’s hand (clearly, he could rule out “weak in diamonds”), doubling 5♥ was the main cause of the poor

N-S result. Even after a forcing pass of 5♥, however, would North really bid 5♠ with such poor spades, limited values,

and problematic diamonds? So the first decision was that N-S’s result would stand. They had ample opportunity to figure out what had happened,

and were unlikely to go right in any event. But for E-W, the rules for an adjusted score are more closely dependent on the misinformation they gave on a straightforward

auction — they should know the meaning of 1♥ – (1♠) – 3♦. There was sympathy and considerable discussion about some kind of adjustment; either a 2 to 3 imp procedural penalty (although the committee generally finds such adjustments unattractive) or an adjusted score. Since we felt it was only between 10% to 25% that N-S would have gone right with proper explanations, we were not prepared to adjust the E-W score to -100 (in 6♥X, the expected result if N-S did compete to 5♠). All other adjustments would be to artificial scores, which we were not willing to proffer. So we decided not to adjust the E-W score, either.

—————————————————————————-

The above is the committee report that appeared in this morning’s Bulletin from the USBF Team Trials. It’s an interesting follow-on to Judy Wolff’s blog of June 15th, and the subsequent discussion about Convention Disruption (CD).

I have the following comments and questions:

1) This committee met after the RR was complete, and presumably therefore knew that their decision would potentially affect the result of the event (or else why bother to hold a committee at all?). This kind of situation always puts extra pressure on the committee and the ruling itself.

2) Why was there not an automatic 3-IMP penalty to EW for CD? They gave vastly different explanations on each side of the screen and put the opponents in jeopardy thereby. That should have been done whatever else the committee chose to do or not to do.

3) North-South “had ample opportunity to figure out what had happened, and were unlikely to go right in any event”. It would be interesting to know what the results were on this board at other tables — did everyone double 5♥? But why is the onus on NS to figure out that they have been given the wrong explanation? And why do they get penalized (effectively) when they fail to do so — they should never have been put in this position in the first place!

4) The committee itself felt that NS might have taken the right decisions as much as 25% of the time given the correct information. Surely, then, there should have been an adjusted score based on that outcome 25% of the time and the table result 75% of the time — I’ve seen that done on a number of occasions in the past.

5) In the end, the committee found reasons not to act — not to penalize EW for CD, not to adjust either NS’s score or EW’s score. Seems to me that if you took a show of hands and asked people whether or not there should be some kind of penalty or adjustment (without determining exactly what it should be) the response would be an overwhelming ‘yes’. So why did the committee fail to act? I think Comment 1 is germane here, and I think they overanalyzed everything, instead of stepping back and asking themselves what needed to be done to restore equity, in so far as they could.

My understanding is that the margin of victory in this match was 1 IMP, so had the committee taken any action at all, it would have changed the result, and in fact affected which teams went on to the KO stages. As Bobby Wolff has written, once CD occurs, bridge stops and the rest is Alice in Wonderland. What a pity that important events are decided in such a way.

|

June 7th, 2010 ~ Ray Lee ~ 5 Comments

One deal from the last session of the CNTC Final on the weekend provoked some heated discussion among the commentators about the relative odds of two lines of play. Since the deal in question was a grand slam, it was of no little importance to the declarer involved. This was the situation in the key suit:

| West |

|

East |

| ♠ |

|

♠ |

|

| ♥ |

|

♥ |

|

| ♦ |

|

♦ |

|

| ♣ |

A K J |

♣ |

7 6 3 2 |

Declarer, playing in 7♥, needed 3 club tricks (obviously without giving up any!). Since he had lots of entries both ways and an available pitch from the West hand, he had two possibilities: a) cash the ace, then take a finesse b) cash the ace and king, then if the queen has not appeared, take his pitch and ruff a club. So the question is — with no other information, which is the better line? And for a bonus, is it significantly better, or is it close?

Most people I’ve posed this question to have opted to try the ruffing line — partly, I think, because no-one wants to make a grand on a finesse, and partly because there’s always the hope of some sort of squeeze if you ruff the club (although on this deal there wasn’t — clubs represented your only possible source of a thirteenth trick). Linda not only selected that line, but offered the opinion that it wasn’t close. Hence this blog. I mentioned on the BBO commentary that the odds were in fact pretty much the same — and everyone disagreed, including a number of spectators. One of them continued the discussion by email, eventually conceding gracefully the next day!

So here’s how it works. Assuming you have no other information (and I’ll get to that in a minute), the a priori odds stack up as follows:

a) cash the ace then take a finesse

You win any time South has the queen (50%) plus a little vigorish for a stiff queen in the North hand (one twelfth of 14.53% for all the 5-1 breaks, or 1.21%) — so 51.21 %.

b) cash the ace and king, then if the queen has not appeared, take the pitch and ruff a club.

You win with a stiff queen in either hand (one sixth of the 5-1 breaks, or 2.42%), a doubleton queen in either hand (one third of the 4-2 breaks, or 16.15%), and clubs 3-3 (35.53%). Add those up and you have 54.1%.

As I said above — pretty close. So is a 2.89% difference enough to hang your hat on when you’re playing a grand slam? Bob MacKinnon discusses this in his recent book, Bridge, Probability and Information: He says, ‘When the odds of two alternatives are nearly 50-50, in a practical sense it doesn’t matter which one is chosen, because the uncertainty is so great.’ You need to take into account everything that has happened on the deal, from the auction and opening lead onward, then take your best shot. It’s rare indeed that this kind of decision is purely a matter of a priori probabilities.

In the real-life deal, it certainly wasn’t, for two reasons. The more practical one was that while we discussing the right line of play in 7♥, the players actually bid to 7NT, where only one option was available — the finesse. Fortunately for declarer, the other reason was that North had preempted over West’s forcing club opening bid and was marked with six or seven diamonds. Thus by the time declarer had to play clubs, the finesse was much better than a 50-50 shot owing to the imbalance in Vacant Places between the North and South hands.

So the moral here is two-fold: if you run into this fairly common situation at the table, it’s pretty much a toss-up — and you should look for every other piece of information you can find to help you choose the line most likely to succeed.

June 5th, 2010 ~ Ray Lee ~ 3 Comments

Watching the CNTC final yesterday, I saw a fascinating deal that reminded me of one I had seen recently, in Peter Winkler’s soon-to-be-published book Bridge at the Enigma Club. While Peter’s primary purpose in writing this book is to promulgate his ideas on encrypted signalling and bidding, as well as his relay methods, he’s put together an impressive and entertaining set of deals for the casual reader. In the one that I was thinking of, declarer needs to find the ♥Q , and knows that South started with either 4-0 or 0-4 in the majors. He manages to bring the hand down to a 3-card ending before making his guess, thereby forcing a major-suit discard out of South, revealing the entire distribution. Effectively, this is a non-material squeeze for information. Keep that idea in mind as you watch what happens on this deal from the CNTC:

| Dealer: E

Vul: Neither

|

North |

|

| ♠ |

A J 10 8 6 2 |

| ♥ |

K 3 |

| ♦ |

A 6 2 |

| ♣ |

Q 2 |

| West |

|

East |

| ♠ |

7 5 |

♠ |

9 |

| ♥ |

Q 8 6 4 2 |

♥ |

J 10 9 5 |

| ♦ |

9 5 4 3 |

♦ |

Q 8 |

| ♣ |

J 4 |

♣ |

A K 9 8 5 3 |

|

South |

|

| ♠ |

K Q 4 3 |

| ♥ |

A 7 |

| ♦ |

K J 10 7 |

| ♣ |

10 7 6 |

In the Open Room, Dan Korbel opened 1♣ , after which North-South bid unimpeded to 4♠ . The play was not very interesting, and declarer scored up 11 tricks. Not so in the Closed Room, where Judy Gartaganis opened the East hand with a Precision 2♣ . Husband Nick found a tactical 2♥ response and Keith Balcombe came in with 2♠. Judy, who had every right to expect more than a 3-count opposite, cuebid 3♠ , and Ross Taylor raised his partner to game. Nick was done now of course, but Judy was not — she pressed on to 5♥. Ross persevered to 5♠ , and everyone finally had had enough.

The defense started with three rounds of clubs, ruffed by West and overruffed by declarer. He drew trumps, cashed his two hearts, and paused to take stock. East was known to have one spade, and probably ten rounded-suit cards. Surely for an opening bid and a cuebid she had at least another queen. On the other hand, she could have the ♥Q, and West was known to have the diamond length. Eventually, declarer finessed into East, conceding a game swing.

Full marks to East-West for pushing their opponents to the five-level, but I think Keith missed an important extra chance here. Remember the story from Winkler’s book I started with? Well, if declarer runs all his spades, what three cards does West come down to? Obviously he must keep three diamonds, or the jig is up. So he’s going to have to part with the ♥Q. Surely now, having seen that card, declarer is going to play diamonds correctly?

It’s an idea I don’t think I’d seen before reading Peter’s manuscript, but obviously it’s one to watch out for at the table — and one that can pay off big-time!

June 4th, 2010 ~ Ray Lee ~ No Comments

Linda and I spent much of yesterday providing BBO commentary for the CNTC semifinals — we found that knowing all the players personally added considerably to the fun for us. As the third quarter started, RR winners GARTAGANIS and dark horse JANICKI were separated by only 4 IMPs, so we settled down to watch that match. At our table, the East-West pair were Gordon Campbell and Piotr Klimowicz, both members of Canada’s IOC-winning team in Salt Lake City in 2000 (that was where Canada had to beat Italy, the USA, and then Poland in the final — no cheap victory), although they did not play as a partnership in that event. South was Jim Priebe, who played for Canada in the 2004 Olympiad, and North was Paul Janicki — a relatively new partnership.

The set started quietly, but soon came to life on the following deal — one whose result was to establish a trend that ended after 18 boards with GARTAGANIS holding a commanding lead. The deal itself looked innocuous when we first saw it come up on the screen:

| Dealer: W

Vul: EW

|

North |

|

| ♠ |

10 5 4 |

| ♥ |

10 4 3 |

| ♦ |

4 |

| ♣ |

A K Q J 9 6 |

| West |

|

East |

| ♠ |

A K Q 8 7 2 |

♠ |

J 9 6 |

| ♥ |

J 7 |

♥ |

A 9 6 2 |

| ♦ |

Q 10 9 6 |

♦ |

K J 7 |

| ♣ |

10 |

♣ |

7 4 3 |

|

South |

|

| ♠ |

3 |

| ♥ |

K Q 8 5 |

| ♦ |

A 8 5 3 2 |

| ♣ |

8 5 2 |

In the other room, Nick and Judy Gartaganis (NS – and also members of Canada’s IOC teams in Salt Lake City) faced Jordan Cohen (E) and Steve Cooper (W). The auction went:

| West |

North |

East |

South |

| 1♠ |

2♣ |

2♠ |

dbl |

| 4♠ |

5♣ |

all pass |

|

|

|

|

|

The defense started routinely with a spade to the ace, and a diamond switch. Nick won this, ruffed a couple of spades in dummy, drew trumps, and led up to the heart honors to chalk up an easy 400. At our table, the auction was reported as follows:

| West |

North |

East |

South |

| 1♠ |

2♣ |

4♠ |

5♣ |

| pass |

pass |

dbl |

all pass |

|

|

|

|

There had been some mechanical problems with the VuGraph feed, so it’s possible that this somewhat unlikely sequence is not accurate. However, the fundamentals remain: East-West bid to 4♠, North-South went on to 5♣ , and East doubled. Just as we were beginning to speculate on whether the contract could be beaten on what seemed to us to be a highly unlikely trump lead, the ♣3 hit the table from Piotr. Declarer won this in hand and played a heart: on this trick, Piotr made his second nice, and highly necessary, play by ducking the ace. If he wins the ♥A, declarer can come to three heart tricks — but more importantly, the hearts give him entries to ruff out diamonds: he gets home with 6 clubs, 3 hearts, and 2 diamonds. Now declarer, in dummy with the ♥K, called for a spade, and it was Campbell’s turn to shine — he ducked his ♠AKQ to allow partner to win the spade and play another trump. After this it was all over — wriggle as he might, declarer was always going to lose the two aces, and either a second heart or a second spade. By now, Janicki could have been forgiven for echoing a famous line from Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid: ‘Who are these guys?’

These days, one checks all analysis with Deep Finesse, and DF of course points out that a low heart lead also beats 5♣. That’s because it allows the defense to maneuver a heart ruff for their third trick unless declarer takes a round of trumps himself, after which a second trump cooks his goose when the defense gets in on a spade. Back in the real world, only a trump lead, followed by the precise defense found at the table, is good enough. My own opening lead choice of the ♠J, to have a look at dummy, would not have worked — the timing is off for both the heart ruff and the trump leads.

From here on, Campbell and Klimowicz were merciless, scarcely making a wrong bid or play, and when the set was done, GARTAGANIS was 60 IMPs up and headed for today’s final.

May 26th, 2010 ~ Ray Lee ~ 2 Comments

It isn’t often a mainstream publisher puts out a book on bridge, and it’s an even rarer event when the author is a well-known writer in other fields. But that’s exactly what’s just happened. Doubleday has just released The Cardturner, by Louis Sachar, the bestselling young-adult fiction author responsible for such winners as Holes (which became a popular movie).

When the story begins, Alton Richards is a fairly typical 17-year-old. He’s in high school, his girl-friend Katie has dumped him for his best friend Cliff, and his parents are bugging him about getting a job for the summer. Then Granduncle Lester calls. Lester is the crusty old relative no one wants to spend time with, but he’s also filthy rich, and the family wants to stay in his good graces, and therefore presumably in his will. Lester needs some help, and Alton, being apparently idle, is duly summoned to the phone by his mother. Lester asks him two qualifying questions: “Do you know a king from a jack?” and “Can you play bridge?”. Alton gives satisfactory answers to these questions (‘yes’ and ‘no’ respectively), and is hired: for $75 a session, he’s going to be Lester’s cardturner.

For Uncle Lester, it turns out, is a keen (and very good) bridge player, despite being blind, diabetic, and quite possibly terminally ill. Alton’s job is to take him to the bridge club three or four times a week, to sit beside him, then to call out and turn his cards. Apparently the previous incumbent, Toni (also a grand-niece, but reputed to be more than a little crazy, so avoided by the family) began to learn a little too much about the game. Finally, when instructed to duck an ace, she stopped and inquired “Are you sure?”, the incident that led to her being replaced by Alton.

Through Alton’s eyes, then, we are introduced to bridge and bridge players. There is a funny incident when he reads out Lester’s cards to him for the first time – and does it in random order (“Jack of diamonds, four of clubs, six of hearts…). Lester yells at Alton for being an idiot, but later realizes he just didn’t know any better, and demonstrates very neatly to him how memory and organization work together: Memorize this sequence, Lester challenges him: g-b-c-d-i-o-a-o-r-y-t-g-l. When Alton admits defeat, Lester says, ‘Okay, try the letters in this order: g-i-r-l-b-o-y-c-a-t-d-o-g.’

At first, Alton is bemused by what he sees: by the game itself, by the people he meets, and by how they behave and talk to one another. “These people are from a different planet, Planet Bridge”, he tells Cliff in his first week of duty. “They even speak their own language.” But gradually, depite himself, he begins to learn about the game, and realize something of its complexity – that it is more than a substitute for bingo for old people.

He becomes more and more interested, and eventually (of course) begins playing himself – with Toni, who we can soon guess is going to become the ‘love interest’, even though she is currently dating someone else. We also being to learn a little about Lester’s past – which contains some kind of mystery involving his former bridge parter, Toni’s grandmother Annabel. It seems some kind of incident occurred at a Nationals, which ended with Annabel in an asylum, and Lester giving up bridge for many years. Annabel’s unhappy life eventually ended in suicide.

The plot moves along briskly, and I’ll leave you to discover for yourself how Alton and Toni get to play bridge at a Nationals (and, of course, finally get together), and what happens there, by reading the book. The fascinating thing is how Sachar has managed to weave the bridge background into a compelling story, without making it inaccessible for non-players (who surely must make up the bulk of his audience). Indeed, as we get to the Nationals, the deals and incidents multiply, and the bridge content gets quite dense.

The key to how he manages this rather neat trick is the little whale icon. This symbol (which is reference to passages in Moby Dick where any teenage reader will just want to zone out for a while) precedes and warns about any detailed bridge section. The reader can then either choose to plow through it, or just skip it by just reading the neat boxed summary at the end of the section – which contains all they need to know to continue with the story. However, the author isn’t in any way apologetic about including all this technical stuff (we get into finesses very early, for example). Here’s what Alton, the narrator, says:

“Bridge is like chess. No one’s going to make a movie out of it. A great chess player moves his pawn up one square, and for the .0001 percent of the population who understand what just happened, it was the football equivalent of intercepting a pass and running it back for a touchdown. But for the rest of us, it was still just a pawn going from a black square to a white one. Or getting back to bridge, it was playing the six of diamonds instead of the two of clubs. Well, there’s nothing I can do about that. I’m sorry my seventy-six-year-old blind diabetic uncle didn’t play linebacker for the Chicago Bears.”

There’s a great bridge background to this story too – not just the play by play parts, but stories about bridge and bridge players. President Eisenhower is in it (Annabel, a Senator’s wife, was a regular at the White House bridge games). Richard Nixon has a cameo too, but not as a bridge player. There are funny stories, and the atmosphere of a bridge tournament fairly leaps off the page.

For me, this book actually accomplishes what Ed Macpherson tried to do in The Backwash Squeeze a couple of years ago: explore and explain the world of bridge and bridge players by following a novice as the game gains an ever-increasing fascination for him. Here, in the hands of a top-class writer, I think the attempt is successful. But I’m too old and I’ve played too much bridge to be part of the intended audience for the book, and it is non-bridge-playing teenagers who will eventually decide whether or not it’s succeeded. People like our eldest grandson, Cassidy, for example.

A couple of years ago, Cassidy (who is a keen player of all kinds of games) discovered that his grandmother was away in China, playing in the World Bridge Championships. He digested this for a few seconds, and then asked his mother, ‘What’s bridge?’. When this was reported to me in due course, I said to Jen, “Aha – got him!”, and she ruefully admitted I was probably right. In any event, there’ll be a copy of The Cardturner heading out to Vancouver pretty soon. If you have teenage kids or grandkids whom you want to interest in playing bridge, this is a book to give them.

I doubt that the IBPA would ever consider The Cardturner for their Book of the Year award, but they should. It has the potential to do for bridge what Searching for Bobby Fischer did for chess.

|

I I Isuppose it was inevitable that the Bennett murder would be included, but at least the write-up emphasized that its real importance was the way Culbertson was able to use the publicity surrounding the case to market the game.

I I Isuppose it was inevitable that the Bennett murder would be included, but at least the write-up emphasized that its real importance was the way Culbertson was able to use the publicity surrounding the case to market the game.